Henry Mancini's Sex Panther

There isn't a whole lot to love about the new iteration of The Pink Panther starring Steve Martin, although I will cop to a bizarre and completely inexplicable fascination with the scene where Martin's Inspector Jacques Clouseau struggles to pronounce the word hamburger ("Der bur-guh!"). And I'll always love the film for providing me with the name of my fantasy baseball team for the 2006 season. But otherwise: garbage (pronounced with the soft 'g' sound so it comes out all French and classy).

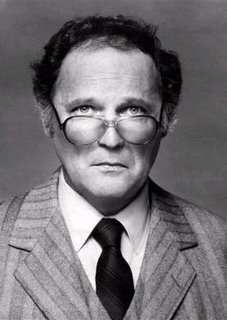

But despite the overall crapuosity of the film, there is one truly transcendant moment and it is animated opening credits where we get to hear the familiar strings and horns of Henry Mancini's unforgettable theme song. You know the one: finger snaps, sleazy sax, and plenty of da-dum dah-dummmmmms.

That this singular moment of pure movie bliss is swiped wholesale from a movie some forty-years old indicates the level of originality of Shawn Levy's Panther. And in much of the rest of the film, Mancini's magic is diluted with completely unnecessary (and occasionally embarrassing) wakka-cha-wakka razzmatazz. Cause, you know, Martin is totally hip and contemporary and stuff (that's why he's chilling with Beyonce instead of Capucine). But in those opening credits, where Mancini's original composition is presented with faithfully jazzy verve, you get a sense of what a good composer can contribute to a bad movie.

Complainers always say they don't make them like they used to. Well they do and they don't: they used to make Pink Panther movies and, as we can see, they still do (at one point, they used to make them with Roberto Benigni, so some things weren't better back in the day). But they used to make movies with remarkable, unforgettable scores, and that doesn't really happen very much lately. When was the last time a new movie offered a really powerful and memorable musical moment? Titanic's coming to mind, but that was a song, not an instrumental, and that was bad, not good.

So kudos to the long dead Henry Mancini for livening up an otherwise uninspiring little comedy. As for the fantasy baseball team, I expect big things from Dr. Knockers' Big-Time Little All-Stars in the upcoming season.