The best Idol ain't on Fox

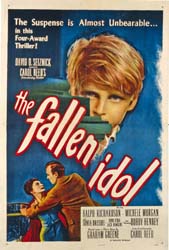

I can't say enough good things about The Fallen Idol, which is playing through next week at New York's Film Forum. It got great reviews — our man Hoberman, the J-Hoba, called it superior to The Third Man in The Voice — so expectations were high. But they were all met and more so.

If I had my druthers I'd just put up some images from the film and describe for you the sheer, simple genius of Carol Reed's camerawork (coincidentally, if I really had my druthers the phrase "if I had my druthers..." would be used a lot more frequently in casual conversation). But I couldn't find any pictures that would illustrate any of the best sequences. So I will do my best without visual aids.

The film is based on a Graham Greene story, but it may as well be based on a play: it is staged almost entirely on a single, multi-story set, a foreign embassy in London where a precocious young boy named Phillipe (Bobby Henrey) lives with his ambassador father (mother's absence is a point of contention throughout the film). Papa leaves for the weekend, and the boy is left in the care of the butler Baines (Ralph Richardson) and his unimaginably cold wife (Sonia Dresdel, who can give Mrs. Danvers a run for her money) who are having, shall we say, marital difficulties.

It is important to note that The Fallen Idol takes place entirely on one set because the film doesn't feel like it takes place on one set. Reed's camera isn't wildly flashly, but it is uncommonly nimble, gliding over bannisters, hiding beneath tables, following a most important paper airplane on its impossibly slow (and deliciously suspenseful) descent toward the waiting feet of an unsuspecting policeman.

It is rare that the sheer compositional beauty of a basic close-up can bring a smile to my face, but one in The Fallen Idol did. To give a little away, a death has taken place in the embassy over the course of the weekend. The victim slipped and fell after she leaned on a window and it gave way and pushed her off a ledge to the stairs below in a such a way that makes it seem as though she was pushed. One of the main characters is a suspect, but we know he is innocent. We also know how the victim fell and he does not. After trying to give the police a cock and bull story of Tristram Shandyian proportions, he relents and tells them the truth as best he knows it: an argument at the top of the stairs, he left, he heard a scream, he came running, bada bing bada boom, the lady was dead at the foot of the stairs. The police tell him the story does not jive because the forensic evidence indicates that she did not fall, she was pushed. Our innocent but guilty-looking suspect pleads his case, desperately trying to think his way out of suspicion, in a shot that Reed stages at the top of the stairs so that the murderous window sits, silently and almost mockingly, just over the suspect's left shoulder. The audience wants to scream "YOU ARE INNOCENT! LOOK AT THE BLOODY WINDOW! IT'S STILL AJAR YOU BOOB!"

As you can see, much of The Fallen Idol's ample delights come from Reed's careful negotiation of the flow of information between characters and the audience. Primarily, he does so by telling the vast majority of the film from little Phillipe's perspective, which might make the film sound a bit like an artsy British Home Alone, and perhaps it would have taken on such a quality if not for the remarkably honest performance of Henrey in the lead. His coy stares and instinctive answers to police questioning strike such a rich chord of truth (not to mention humor; one of the few things the reviews I read left out was just how dryly funny the movie can be at times) that I was absolutely flabbergasted. As moviegoing adults we are sort of insulated from cuteness, particularly in children and small woodland creatures. We know not to be seduced by their hollow charms. But Henrey is utterly disarming and totally lovable. He doesn't seem like a child actor acting childish, he seems like a child being a child.

I could ramble on and on and on, drunk as I am on movie love, but it would really work much better with the pictures. Then we could explore Reed's motif of vertical bars (the stair railings, the zoo Phillipe visits, even a pattern on a blanket in a key scene), or discuss the scene where a terrified Phillipe runs through the nightime London streets in a sequence that feels, as our own James Crawford astutely observed, "like a dry-run for The Third Man," or show some of the great subjective camera work and canted angles that put the audience completely, helplessly in Reed's control. When the DVD comes out we'll do this all again with some hot screengrab action. But if you are within spitting distance of Film Forum, get your ass in gear.

3 Comments:

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Curses! I was going to post today, but The Singer beat me to it. Nicely put, but I might add something, regarding that exquisite nighttime run through London backalleys (okay, so the film isn't really on one single set, but it might be). It's remarkable from an auteurist standpoint, being something of a rough sketch of the delirious final chase through Vienna's sewers in The Third Man, (which was released in the UK one year after Idol) but also for the way it radically changes the film's register. When Philipe "witnesses" Mrs. Baines's fatal fall, he runs out into the night, wildly, haphazardly careening (as much as a little stubby-legged tyke can careen, no less wildly or haphazardly) down streets, visibly distraught with the belief that his boyhood idol has committed some grievous as. The screen turns from the muted middle tones of the embassy to stark chiaroscuro. Blinding white lights cast deep fathomless shadows, spilling over cobblestoned streets, turning wrought-iron gates into prison bars (as Mr. Singer mentioned in his post), and making every doorway into a potential coven for some kidnapper. But instead of the expected abduction (one of many times that Carol Reed concludes a scene in a manner contrary to our expectations), Philipe runs into a policeman, who takes him into custody, and out of this terrifying scene. The entire movie is filtered (or, to use a high fallutin' cinema studies term, "focalized") through Philipe, restricting all the information we receive to what the little child could know, but his anxiety-inducing ramble is the only place in the film where the camera becomes truly subjective. Frenzied cutting and nightmarish noir cinematography turn the alleys into an articulation of Philipe's aggrieved mind, in the best tradition of German expressionist cinema. It's fairly stunning to see the visual tradition of film noir, the playground of Sam Spade and Harry Lime, use to convey how a little child thinks and feels--how the world can become a horrific phantasm through simple misunderstanding.

Now that's a comment.

Post a Comment

<< Home