I've never been to Texas. Neither has Wim Wenders, or at least not really. In his Voice review of "Don't Come Knocking", Michael Atkinson succinctly knocks Wim down a rung, describing his work as "besotted with American cliché culture, from trench-coat noir and road-movie outlawry to rockabilly and post-western macho-ness, all of it commonly orchestrated with a whiskeyhead's dreary notion of cool and lousy sense of direction."

The new film, which reunites Wenders with true-west native Sam Shepard, sounds like more hokey drivel from a German armchair cowboy who hasn't created anything worthwhile in about two decades -- so why am I sympathetic? Like I said, I've never been to Texas, but I love "The Searchers" and "Rio Bravo" and "Red River" and Cormac McCarthy with a borderline-obsessive vigor that belies my status as a big-city homebody with a plumber's sense of nature. We're like John Wayne at the end of "The Searchers", Wim Wenders and I, destined to remain outside that door...okay, this analogy doesn't quite work. We're not quite tourists, though. We just know that the idea of Monument Valley -- the image of it -- is a lot more beautiful than the reality of roaming around for five years on a quixotic, dirt-caked, racist odyssey. I would get thirsty.

Which is sort of what "Paris, Texas" is about.

[I rented the movie a few times as a kid, tantalized by the prospect of visiting two foreign cinematic locales for the price of one, but the VHS edition has been out of print for years. Last summer, I found a brand-new $3.99 DVD at Tower Records, and traded my lunch money for some of the prettiest "cliche-culture" cash can buy.]

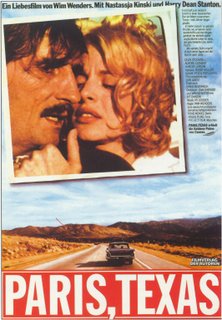

Wenders' 1984 Palme D'or-winning, Sam Shepard-scripted Sauerkraut Western (also see: Fassbinder's "Whity") is a vision of a polyglot American West that can only exist in the mind of a European outsider. A doctor on the Texas border speaks with a German accent. A lead character's wife is French. The Southern sweetheart that Travis (Harry Dean Stanton) sets off to reclaim is played by the quintessentially-European Nastassja Kinski. Travis calls attention to his mother's Spanish origin, and sings a Spanish-language ditty while washing the dishes. Shot through Robby Muller's lens, the sunsets looks a bit too orange, all the motel-room colors a bit too distinct, breathtaking vistas too omnipresent. Ry Cooder's jagged, plaintive slide-guitar score -- the best movie music ever -- still sounds more "Western" than Western.

Like Wenders, Travis is searching for a paradoxical space both primal and cultivated. A home that exists only on a postcard. As he explains, Paris, Texas is the spot of his conception, and the root of a joke his father told in order give his plain mother a sense of cosmopolitan mystique. "This is the girl I met in Paris--[pause]--Texas." Of course, Paris and Texas cannot coexist, except on a movie screen. "It's close to the Red River," Travis adds, drawing a parallel that's closer to Hollywood than the Rio Grande.

Loosely borrowing the paradigmatic quest of "The Searchers", Wenders' film follows Travis' attempt to reunite with the wife and son he abandoned for four years of walking the earth. Finding his son (played by Hunter Carson, son of L.M. Kit Carson, who co-wrote the movie and once starred in the magnificent "David Holzman's Diary"), living with his brother Walt (Dean Stockwell) and his wife in Los Angeles, proves simple and sentimental enough. Tracking down his belle involves a road trip to Houston and a den-of-sin confrontation fraught with extra-textual significance.

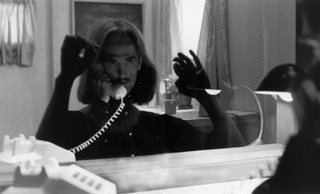

In the famous scene -- recently retooled for a confession-booth effect in Neil Jordan's "Breakfast on Pluto" -- Travis speaks to his once-idealized, now fallen sweetheart through a two-way screen, as Kinski sits in a decorated room playing a "role", presumably for erotic purposes. The set-up emulates both Wenders' approach to his ideal West, his Paris in Texas, and the detached viewer's passive intake of cowboy mythology. At the precise moment that Travis turns the lamp on himself, allowing her to see his face, he gives up his woman, his son, and all pretense at the idea of a family reunion. It's the final scene of "The Searchers", with a dimming screen instead of a closing door.

Over the course of the film, we watch Travis develop from an idiosyncratic but likeable mute into a damned man capable of extreme violence. John Wayne's got grit, but Harry Dean Stanton's riff on Ethan Edwards is subtler and scarier. We can point to more than a handful of great films that announced the Death of the Western, but maybe the mythology only exists to be quashed, resurrected, and quashed again.

In one beautiful scene, Walt asks a nervous Travis to take a plane back to Los Angeles. Travis' earthy, logical, quizzical, downright cowboy response: "Leaving the ground -- why?"