Directed by John Ford (1971/2006)

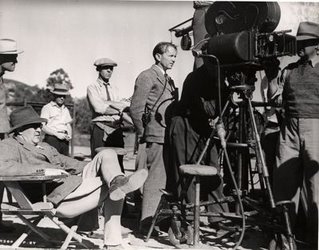

In his documentary about the films of director John Ford, Peter Bogdanovich gets many people, from collaborators to admirers, to speak about the impact and greatness of John Ford. Everyone, it seems, wants to celebrate this gargantuan talent of the movies except one man: John Ford. In Ford's interview (filmed, naturally, with Ford seated in his beloved Monument Valley), he dodges, ignores, or scoffs at every serious or provocative question Bogdanovich asks (Example: Bogdanovich: "Would you say that the view of the West in your work has grown progressively more melancholy? If, for example, we compare the West's presentation in Wagon Master and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance?" Ford: "No.")

Those who knew Ford admit he was a tough interview: if he felt like it, he would often give a reporter the opposite answer to the one he would want to hear. This was almost certainly the case with Bogdanovich, but I think it also speaks to the sort of artist Ford was. Directed by John Ford features marvelous period interviews with three of Ford's best leading men: James Stewart, Henry Fonda, and, of course, John Wayne. All three discuss Ford's techniques for directing of actors, which involved very little concrete discussion and more subtle provocation; Stewart relates a marvelous story of how he motivated Stewart and co-star Richard Widmark to each bring their best to a crucial scene in Two Rode Together by taking them each aside and suggesting the other was their better as a "country actor." When actors would ask specific, pointed questions about their characters, Ford would refuse to answer: he would rather talk fishing or politics or anything else, Fonda suggests, implying that even if Ford was messing with interviewers like Bogdanovich, it may have been more involuntary than it might have first appeared.

This jives with my opinion that while some artists are quite deliberate and methodical, there are others, just as gifted, who rely instead on instinct and feel. These men and women won't discuss their technique, or their worldview or whatever with an interviewer because they can't: creation for them is some sort of alchemical process that exists at least in part outside their full control. They are naturals. Ford was a natural. It was simply in his nature to do what he did, and to do it as well as he did. One of his admirers, Scorsese I think, mentions that wherever he put the camera in a scene was always the correct place to put it.

For an artist like Ford, to examine their gift too closely is to become too self-conscious of it — something that's happened to many directors of early success who've taken their talents too seriously. Soon an inflated sense of self-importance creeps into their work. Mr. Bogdanovich himself might know a thing or two about that.

Ford was able to remain a filmmaker and not a self-analyzer and his remarkable career stands as a testament to that. Bogdanovich's documentary is a little too long and a little too reverent, and I have a hunch Ford would have never put his name above the title of a picture with such a loose structure, but it does feature more beautiful images than you can count, references to movies you haven't seen and should (TCM, thank you for showing Fort Apache!), and those terrific interviews with Stewart, Fonda, and Wayne (who understands Ford better than anyone else Bogdanovich speaks to), along with some of his filmmaking fans, Steven Spielberg, Walter Hill, Martin Scorsese, and Clint Eastwood. Watching Clint paired with those clips of Liberty Valance made me think of Flags of our Fathers more than once. We've discussed it quite a bit over on Michael Anderson's Tativille, but is it too late to get into it in Fordian terms?

The one really truly great nugget Bogdanovich manages to pry from Ford: his opinion of dialogue. As a truly visual filmmaker, Ford tried to limit the dialogue as much as he could but, as he acknowledges, a certain amount of it is expected by the audience and therefore a requirement. "Do you like dialogue?" Bogdanovich asks. "Yeah," Ford replies, "if it's cryptic enough."

4 Comments:

No, it's not too late to discuss Eastwood in "Fordian" terms, but I really don't think FLAGS OF OUR FATHERS is the most productive place to do so: in fact, there are few films that resemble Ford's work less than this modernist amalgam. Eastwood is at his most Fordian when he is critiquing American myth through classical exposition, albeit with a sometimes violent and even profane inflection. Think WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART, think UNFORGIVEN (obviously), think A PERFECT WORLD. But don't think FLAGS OF OUR FATHERS. The others are the next logical moment in the evolution of Hollywood classicism post-MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE. (A PERFECT WORLD really is a movie of the early 1960s -- its setting.) FLAGS OF OUR FATHERS on the other hand has nothing to do with this formal sequence.

It's always about the formal with you.

How about the fact that Flags of our Fathers is almost a tonal sequel to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance? And that it shares a similar critique of the classic line from Liberty Valance: "When the legend becomes truth, print the legend." ?

While I certainly agree that the structure is not one that resembles Ford's films, I think Eastwood (and Spielberg, producer of Flags and another talking head from Directed by John Ford) would acknowledge their debt to Ford, and specifically Liberty Valance in making this war picture. Maybe Fort Apache too, based on what I saw in Bogdanovich's doc last night, but since I haven't actually seen that film yet I can only speculate for now.

I for one, didn't think the modern footage added enough to the doc. There were a few great stories, like of Speilburg meeting Ford as a youth. Otherwise the new interviews were staged like every other interview, too much talking heads. Compared to that of say Henry Fonda, who would stand up, walk around, and make us feel involved in the recolections. I just saw "Seven Plus Seven" (part of the Up Documentaries) and each interviewee was given a place to talk that seemed to fit their mood. Roger Ebert noted that interviews used to be much more personal and telling, and I think the difference between the old interviews and the new in this doc shows this.

An interesting point. I guess I'm so desensitized to uninteresting interviews that it didn't much make a difference to me (though I did observe that so many of the interviews seemed to have been shot in the same spot).

Post a Comment

<< Home