Comedy

People get overlooked. All the time. Like tonight the open-hearted jokester at the open mic night at my local bar got overshadowed by some pretentious dudes with beards and hats. They weren't close to being as honest about their insecurities and obsessions, but chose to cloak themselves in dense metaphors and ethereal melodies. They were hollow.

All just to say that taste is a rare commodity, and it's possible for brilliant directors to fall through the critical cracks. Like Sacha Guitry, for example. Guitry, a successful French theatre director, went on to make brilliant comedies, and I'm sure is well known in his native land. Few of my cinema literate friends seem to be aware of him however.

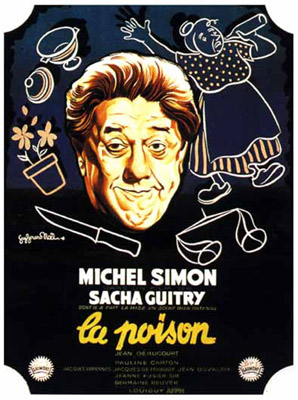

His style is unique, relentlessly self-reflexive, starting with the opening credits, which disregards printed titles for a Guitry voice-over and images of his crew, whom he roundly satirizes. In the film I saw tonight at MOMA, La Poison, he calls up an actress on the phone and tells her she won't get a credit because he cut out her speaking scene. All before the film begins. Orson Welles readily admitted he stole this technique from Guitry for his Citizen Kane trailer as well as his later essay style films F For Fake and Filming Othello.

La Poison tells the story of a small town, and of the hatred of a husband and wife. Both plan ways to kill each other, and only Michel Simon succeeds. The formal techniques are stunning, here it's the repeated usage of the radio. A popular radio drama plays as the couple sits silently at their meal, the wife pounding a bottle of wine as per usual. The neighbors hear the dramatic argument from the show and think it from the couple. Their relationship is encapsulated in the diegetic sound and in their expressions. Later, a defense attorney is interviewed on the radio, giving his views on the difference between murderers and assassins, and his clear conscience at achieving 100 straight acquittals. All this before brilliant intercutting between the the events of the town and the husband's repeated entrances to his wife's drinking. Tragedy is comedy sometimes. Here it's hilarious.

So there's the parallel between the radio and and the couple, and later, during the husband's murder trial, there's a parallel between the children and the murder (all the parents are at court watching) as they reenact the knifing as they play husband and wife. It's a critical look at both media exploitation of murder trials and a brilliant display of crosscutting, as the husband defends his actions to the children doing their own murder demonstration.

The humor is so dark it's astounding. Early in the film a group of townspeople go to the priest to explain how their village needs an attraction, a reason for people to visit. So they propose he take a mentally-challenged girl and pretend to perform a miracle on her, because she'd believe anything he'd tell her. And it's funny.

The biggest coup is the court scene, where Michel Simon defends his actions to the court, his main defense being the fact she was attempting to kill him first, and also that she was ugly. He passes around a photo of her to prove just that.

And yet the film remains jovial, loves its characters, and is joyfully immoral. It's really a miracle.

And his Story of a Cheat is even better!

1 Comments:

Sounds funny, but not Herzog funny.

Post a Comment

<< Home