Dial B For Blog

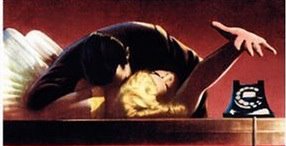

With a single gesture — Grace Kelly, arm outstretched, desperately reaching into the audience for help — Alfred Hitchcock exploits all that is great (and rarely utilized) about 3-D filmmaking.

For a 3-D film, Dial M For Murder is surprisingly restrained. Most 3-D pictures rely on subjective camera angles to shock the audience, putting them, for instance, in the position of a murder victim as they get assaulted by a pointy and impossibly large knife. Hitchcock's use of 3-D is primarily in the pursuit of eliminating the distinction between the people in the audience and the characters on the screen: he plays with layers of distance, obstructing our views of the players with furntiture or liquor bottles. The carefully constructed space invites us to feel like an additional member of the cast.

For a 3-D film, Dial M For Murder is surprisingly restrained. Most 3-D pictures rely on subjective camera angles to shock the audience, putting them, for instance, in the position of a murder victim as they get assaulted by a pointy and impossibly large knife. Hitchcock's use of 3-D is primarily in the pursuit of eliminating the distinction between the people in the audience and the characters on the screen: he plays with layers of distance, obstructing our views of the players with furntiture or liquor bottles. The carefully constructed space invites us to feel like an additional member of the cast. Where most filmmakers use 3-D to assault the viewer, Hitchcock uses it to unnerve them. He never places us in the position of Grace Kelly's character, who is attacked by a man her husband has hired to kill her, nor does he put us in the killer's shoes when Kelly manages to defend herself and stab him with a pair of nearby scissors. Instead, we maintain our position as observers, forced to watch in great suspense as Kelly unwittingly approaches a ringing phone that is the signal for the murderer to attack. When Kelly plunges her arm towards us it is not to scare us but to upset us: for nearly an hour we've grown accustomed to the visual sensation of being inside this flat with Kelly and her conniving husband. That one movement shatters the illusion in a beautiful way.

Dial M is frequently referred to as minor Hitchcock; in 3-D it's a lot tougher to dismiss. Photographic trickery aside, it also boasts one of Hitchcock's most supremely likable murderers, Ray Milland's untouchable Tony Wendice. It's certainly superior to Rope, and might even give Lifeboat a run for its money. It's playing five times tomorrow at New York's Film Forum. It is not to be missed.

Also, on a somewhat unrelated subject; plenty have called Woody Allen's Match Point a Hitchcockian thriller — Dave Kehr even compared it to Frenzy — but has anyone noticed how much of a debt it owes to Dial M For Murder? In both, a former tennis star marries into a life of wealth, finds his position jeopardized by infidelity, and realizes murder may be his only way of maintaining his position.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home